I had the opportunity to go to Baghdad last summer under the Frank Israel Memorial Scholarship, from which the excerpt on the screen is (Click here for blog). In selecting a topic for my graduate thesis, looking at a place like Baghdad was opening up pandora’s box. With so many infrastructural and basic needs, due to endless war, previous sanctions, and current turmoil, I found it challenging to select a project type. I knew that a cultural institution was of interest to me, as I believe cultural buildings are critical in Iraq’s social revival. In Baghdad, I noticed a pattern that ultimately informed my direction: after every cup of chai with a neighbor, there was a story. With every secret and culturally taboo late night conversation with the soldier who lived outside of my house, there was a story. The endless undocumented stories came from different sects and ethnicities, yet ended at the same conclusion: loss. That’s why, for my thesis, I am designing a war archive, 2003-present day Iraq.

To further clarify my role in a land that desires architecture without infrastructure, I decided to play the role of the architect/educator--this is to clarify my intent and narrow my scope.

In beginning my research, I looked up a timeline of documented political events, as seen in the background, along with death tolls of Iraqis, the larger numbers on the screen. The statistics are a direct function of the political events they rest on.

For each of the numbers is a name. Diagrammed is a graphic of Iraqi deaths since the inception of the war, juxtaposed against the recorded names and locations of those whose lives were lost in the months of April and May of 2010. I did this to grapple with the fact that each of those numbers was attached to a human who lived a life and had a family and dreams and hopes.

Architecture in Iraq must be considered in a large historical trajectory—from colonialism to modernism to the rise of Iraq as a nation state to today’s postcolonial search for local identity. Architecture, often iconic of Iraq’s national identity, has been closely tied to Iraq’s political climate since the country’s birth in 1921, which was the topic of my research paper for 691 in the fall. In Iraq, the official design emphasis wavered from stressing Iraq’s pan-Arab ties to stressing an identity concentrated more on Iraq’s Mesopotamian heritage. However,

between the wavering design languages, the rise of the political monument under Saddam, and the wars that destroyed much of the built environment, Iraq sits in an architectural design vacuum today.

Like architecture, current Iraqi national identity also falls in a vacuum. One cannot characterize Iraq as a people, with the far right, the far left, and the majority uninterested in polarized politics. What ties those in the all three political ideologies together is the most human form of feeling and experience, and namely, loss—the point at which my thesis proposal begins on.

Archives have been repositories of international remembering for most of human history. The war archive is to serve as a monument to the people, and it is to play a pivotal role in the lost history of Iraq. In the war archive, unlike a typical museum, the people of Iraq become the artifacts. The three goals for the Iraq War Archive become to preserve, share, and search for Iraqi history.

So I am going to introduce the site. The site is in Asia, more specifically, the Middle East, in the country of Iraq, the capital of Baghdad, and the district of Karkh.

Site selection--I did an analysis of 4 sites to find that the first site is the best selection economically, practically, and for the site’s purpose.

The site is adjacent to the Iraq National Museum, 3 major monuments, and walking distance from a public space. I avoided development on the large and empty space between the site and the Baghdad Train Station, as I found a space adjacent to a rail yard more suited and opportune for an economic development rather than a cultural institution.

3D rendering. The non cultural buildings around the site are low income housing. When the museum was planned for the site in the 60s by a German architect, construction took longer than anticipated. As a result, the area became awash in car repair shops and low income housing rather than learned and cultural institutions that typically surround national museums. Today, the area is a fusion of the cultural and the blue collar.

Case Study. I looked at three different projects to determine my program, beginning with Bernard Khoury’s b018 nightclub in Beirut. This project relates to my project as the site itself has a heavy precedent in war and colonization. As a result, Khoury boldly stated that he “refuses participate in the naive amnesia that governs post-war reconstruction efforts.” His response is quite literal, as the electronic music club is designed like a bunker.

Coop-Himmelblau’s Museum de Confluence in France houses an anthropoligcal collection and focuses on education. The building features the crystal, which is the glass juxtaposed by the dark cloud, or the obscure space of hidden currents and countless transitions, implies that nobody knows what tomorrow may bring. The message: this is a place of discovery..

The Jewish Museum Berlin is my final case study, as the program of the museum archives trauma in a physical way. Libeskind referred to the submission as “Between the Lines,” as it combined a visible, tortuous, and continuous line with a hidden, straight, and interrupted line—and each line served to represent the Jewish experience in Berlin. The formula used for the design included zigzags for the visible lines. Hidden lines were physically represented by six 90-foot high empty spaces referred to as “voids.”

In program, I intend for the archive to be (1) functional and (2) anecodtal. While the bottom floor is reserved for traditional archiving, the top floor is a space to explore and input the history of Iraqis. I choose to submerge the functional archive underground, as archives must meet very specific environmental needs, such as a temperature of 68 degrees and a relative humidity of 40%. Archives must also be careful with sunlight. Security is critical. These needs all pushed me towards submerging the working and archival spaces to protect the information archived. The top floor, which is to feature specific archived materials and physical relics, has more architectural opportunities.

After research on the programmatic and spatial needs of an archive, the FAR indicates that the entire building will be roughly 48,000 SF. Information on specific materials used in the best interest of the building type can be found in your booklet.

The Iraq War Archive creates an opportunity to preserve, share, and search for war related content of a people who were silenced by dictatorship until they were silenced by war. However, the archive proposed does not conform to strict archival guidelines. The Iraq War Archive responds to 21st century technologies, and fuses digital memory with physical memory. With this electronic archive, interactive users can easily enter and edit the archive, and the archive itself can be expanded by the nature and distribution of its users—making the archive an open ended collective building project.

Questions of preservation/censorship of war. Process versus outcome. The process of war, the outcome of war, and the memory of what was.

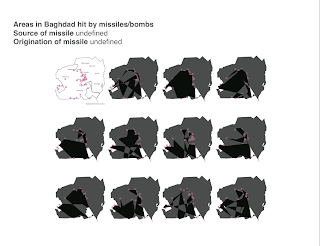

So in determining my design methodology, I decided to derive lines based on ballistic missile projections in the Baghdad sky. Like the questions on the previous page, is it the direction and aim of the missile or the outcome of the missile that defines a war.

I tried obtaining maps of the missiles from the US army and was unfortunately denied access.

My methodology is based on a “scab” versus “scar” technique. Spaces voided by destruction becomes scabs or scars. A scab is the first layer of reconstruction, shielding an exposed interior space or void, protecting it during transformation. Placement of a scar, a deeper level of reconstruction that fuses the new with the old— reconciling then without compromising either in the name of unity. The scar is a mark of pride and of honor, both for what has been lost and what has been gained. It cannot be erased, except for cosmetic means—nor can the scar be elevated beyond what it is: a mutant tissue.

The city of self-responsible individuals, each of whom tell a personal story. exhibits its unique scars as well as its transformations in solitude. The scars of the city are a result of the projectile patterns of the missile. Since I was denied access to the information that was deemed classified, I had to resort to bomb blast sites in Baghdad--sites indicated in pink.

As a design methodology, I will find the scars of Baghdad—as defined by areas that have suf- fered major bomb blasts—and will connect the scars as a method of deriving lines for my final design.

At this point I thank you for your time and welcome any questions.

![love and [fash]ism do thesis](http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_QpTvFF9mI10/TFzrSVrAwZI/AAAAAAAAAqY/Ou8tF__D34w/S1600-R/Blog+Title+4.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment